05 Sep The impact of depression in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma

Mental health disorders and chronic respiratory diseases are two of the leading causes of disability and morbidity worldwide – ranking first and seventh, respectively. A recent World Health Survey (WHO) indicated that depression comorbid to chronic disease impairs quality of life, decreases physical functioning, and increases social isolation and healthcare utilization.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and asthma are the two most common respiratory diseases that impair quality of life in old age. The WHO estimates that over 210 million people are living with COPD worldwide. COPD is projected to be the third leading cause of mortality and the seventh leading cause of burden of disability worldwide by 2030. Despite increased awareness of the impact of chronic diseases on older patients, depression is often under-recognized and untreated in patients with COPD and asthma. Unrecognized and untreated depression in older patients with COPD and asthma may lead to poor prognosis and health outcomes. Greater insight into the consequences of depression in these two conditions may help clinicians to provide (devise) appropriate support and treatment plans for patients and their caregivers.

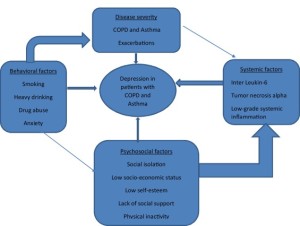

The prevalence of depression in patients with COPD has been estimated at 8–80% and in asthma at 13–32%, respectively. These apparent wide discrepancies in prevalence estimates across studies may be due to the use of different diagnostic tools (e.g. screening scales compared to psychiatric diagnostic tools), respiratory illness severity, cultural issues and settings of the studies (e.g. hospital- or community-based patients). Depression is significantly more likely in older patients with COPD or asthma compared to older people without these disorders. Over 40% of older patients with COPD and 19% of asthmatic patients who are clinically stable experience, clinically significant depressive symptoms that may warrant medical intervention and that interfere in their daily activities and self-management of their respiratory condition. The exact mechanism or pathway by which COPD and asthmatic patients develop depression is uncertain. It is most likely the complex interaction of physical, behavioural, physiological and systemic inflammation that may contribute to heightened risk of depressive symptoms as illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD and asthma are common, exerts significant burden to patients and their caregivers and leads to increased disability and healthcare cost. Iyer and colleagues examined, in an observational study (n = 422), the risk factors for both short term and long-term hospital readmission due to acute exacerbation in patients with COPD. They showed that patients with depression are at 3.8 times the risk of readmission at 30 days and about 2.5 times the risk of readmission at 90 days, respectively. In a retrospective cohort study, Hasegawa et al. examined the age-related differences in rate, timing (n = 301, 164) and principal diagnosis of 30 day readmissions in adults with asthma. The overall prevalence of readmission was 14.5%. They stratified their patients into three age groups: younger (18–39 years), middle aged (40–64 years) and older (>65 years) adults. The prevalence of depression in hospitalized for asthma exacerbations in younger patients was 7.7%, middle aged was 13.9% and older adults was 11.0%, respectively. Furthermore, compared with younger adults, older adults had significantly higher readmission rates (10.1% versus 16.5%, with odds ratio, 2.15 (95% confidence interval 2.07–2.13). The readmission rate was highest in the first week after discharge and that approximately one-half of readmissions were due to diagnoses unrelated to the index admissions, with older adults having a higher proportion of non-respiratory diagnoses. This signify older adults with asthma had higher rate of readmission and elevated depressive symptoms compared to younger adults. Future studies should examine the assessment and treatment of depression in older asthma patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbation.

There is some evidence to suggest that psychological interventions such as CBT can be considered with or without antidepressant treatment for patients with moderate to severe COPD or asthma with comorbid depression. However, resources for this valuable treatment are scarce. For example, a recent national survey that examined the provision (by General Practitioners [GPs]) of psychological treatment including CBT for patients with COPD and comorbid depression in England. GPs reported that barriers for treatment of comorbid depression in patients with COPD include lack of adequate provision of psychological services and long waiting times for psychological treatment.

Depressive symptoms are common in patients with asthma and COPD. They are often under-recognized and inadequately treated. Depression is a predictor of 30-day and 90-day hospital readmission in older adults with asthma and COPD, accordingly. There is some evidence to suggest that pulmonary rehabilitation and cognitive behavioural therapy are beneficial to alleviate depressive symptoms in the short term for patients with asthma and COPD. However, their long-term benefits are uncertain. Thus, prospective well-controlled randomized controlled are trial are needed.