24 Jul Not all home sleep studies are the same

Portable sleep testing for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA)

Sleep studies use a polysomnogram (PSG) to record physiological sleep data. Portable testing (PT) has been used as an alternative diagnostic test for obstructive sleep apnoea based in part on the premise that it is theoretically less expensive and quicker to deploy compared with in-laboratory PSG[1] (type 1 PSG).

Not all portable sleep studies are the same.

There are two broad categories of home sleep studies: Polysomnography (type 2 PSG) and Limited channel sleep studies (type 3 & 4)[2]. Only type 2 portable studies use polysomnograpy with recorded sleep. These type 2 portable PSG devices use unattended polysomnography, i.e without trained sleep laboratory staff observing the data. They record a minimum of seven channels including EEG, EOG, chin EMG, ECG or heart rate, airflow, respiratory effort and oxygen saturation. This type of monitor allows for sleep staging and therefore calculation of an AHI or RDI. It is configured in a fashion that allows studies to be performed in home[3].

A higher success rate is generally obtained when type 2 studies are set up by experienced personnel.

Australian guidelines; the limitations of portable testing[4]

Patients who may be unsuitable for Type 2 Diagnostic studies:

Patient related factors

- Neuropsychological

- Severe intellectual disability (this may also be an issue for type 1 studies)

- Neuromuscular disease

- Major communication difficulties

- Severe physical disability with inadequate carer attendance

- Home environment unsuitable – a number of factors need to be considered including noise level, partner/ family interactions, distance from sleep lab and the safety of any attending staff.

- Discretionary

- symptoms or results of former testing do not equate with clinical impression

- Patients seeking a second opinion where the original diagnosis is uncertain.

- where “serious” medico legal consequences may be relevant

Sleep disorder related factors

- Parasomnia/ seizure detection requiring infrared camera or extended EEG montage

- Transcutaneous CO2 monitoring required

- Where video confirmation regarding body positional/ rotational aspects of sleep disordered breathing is essential

Current guidelines (American) for portable sleep testing based on the Portable Monitoring Task Force 2007[5]:

- Portable Testing may be used as an alternative to PSG for the diagnosis of OSA in patients

- With a high pre-test probability of moderate to- severe OSA

- For whom in-laboratory PSG is not possible due to immobility or critical illness.

- Portable Testing is not appropriate for the diagnosis of OSA in patients

- With significant comorbid medical conditions such as advanced cardiopulmonary disease that may degrade its accuracy

- With evaluation showing suspected of having comorbid sleep disorders

- With screening of belonging to an asymptomatic population

- At a minimum, these devices must record air flow, respiratory effort, and pulse oximetry. (type 2 studies have a lot more than this)

- Device application, education, testing, scoring, and interpretation must be performed under an AASM-accredited comprehensive sleep medicine program.

- A negative or technically inadequate home sleep studies in patients with a high pre-test probability of moderate-to-severe OSA should prompt in laboratory PSG

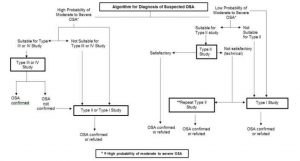

Figure 1. Algorithm for diagnosing suspected OSA.

*. There is variability in the definition of moderate to severe OSA. Readers should note in some articles it is listed as an AHI ≥ 15 (67) and in others an AHI ≥ 30 (76) based on the AASM Chicago criteria of 1999 (16). A variety of clinical tools can be used to divide patients into high and low probability for moderate to severe OSA. ** NB A repeat Type 2 study is unable to be billed via Medicare within 12 months of the original test.

References

- Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3(7):737–47. Cited by: Kundel, V., & Shah, N. (2017). Impact of Portable Sleep Testing. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 12(1), 137–147. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.10.006

- Douglas JA, Chai-Coetzer CL, McEvoy D, Naughton MT, Neill AM, Rochford P, Wheatley J, Worsnop C. Guidelines for sleep studies in adults – a position statement of the Australasian Sleep Association. Sleep Med. 2017 Aug;36 Suppl 1:S2-S22. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.03.019.

- Ibid

- Douglas JA, Chai-Coetzer CL, McEvoy D, Naughton MT, Neill AM, Rochford P, Wheatley J, Worsnop C. Guidelines for sleep studies in adults – a position statement of the Australasian Sleep Association. Sleep Med. 2017 Aug;36 Suppl 1:S2-S22. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.03.019

- Kundel, V., & Shah, N. (2017). Impact of Portable Sleep Testing. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 12(1), 137–147. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.10.006