29 Jul Prediction of Maternal Sleep-Disordered Breathing

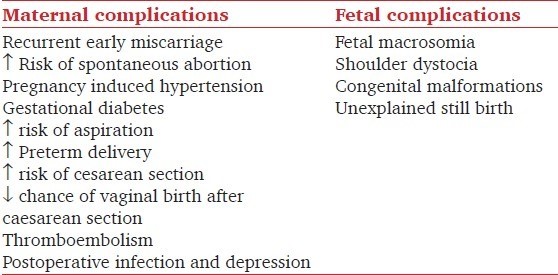

A newly published study has addressed the limited ability to identify women at high risk for sleep disordered breathing (SDB) during pregnancy with an evaluation of the predictive ability using anthropometric measures, other than BMI and gestational weight gain.

SDB has been shown to affect almost 10% of premenopausal women. Prospective data from pregnancy show that 4% of all women have SDB in early pregnancy. However data from samples of pregnant women with obesity or medical or obstetric complications show that the prevalence of SDB is as high as 70% in some studies.

In Australia the screening for SDB during routine pregnancy risk is not consistently performed, and is not included in the Australian Dept of Health guidelines.

Women who are recommended to have further screening and care include those who are overweight, in addition to those with cardiovascular, renal, mental health plus other complex issues including complicated prior pregnancies, major surgery plus psychosocial factors.

To date, screening questionnaires that have been validated in the general non-pregnant population have failed to reliably predict objectively measured SDB in pregnancy. In addition, performance of these screening questionnaires are influenced by gestational stage, with screening tools performing better in the second and third trimester than in the first trimester.

Models that include body mass index (BMI), age, snoring, and hypertension have been proposed in the general and high-risk pregnant populations (Epworth Sleepiness Scale, STOP-BANG), however the ability to predict SDB in pregnant women with obesity and those at risk for pregnancy complications has remained limited.

An important predictor of SDB in the general population includes change in neck circumference from the standing to the supine position, waist circumference and visceral and abdominal fat rather than BMI alone.

During pregnancy early weight gain, biceps and triceps skinfolds and waist circumference positively correlate with metabolic abnormalities associated with OSA.

Specific anthropometric measurements in pregnancy are not synonymous with the same measurements taken outside of pregnancy for many reasons. Weight gain and weight deposition differ by gestational age and although early weight gain may be due to fat deposition, weight gain later in pregnancy is related to an increase in amniotic fluid, plasma volume, and volume of products of conception. In addition the presence of sex hormone receptors will affect the upper airway.

Given the current limited ability to identify women at high risk for SDB to guide a referral for polysomnography or sleep apnea monitoring, an evaluation of the predictive ability of anthropometric measures is warranted.

This new study examined the following anthropometric measures with overweight or obese women in their first trimester of pregnancy (gestational age <14 weeks):

- BMI plus neck circumference (level of hyoid bone) in sitting and supine positions,

- breast circumference measured at widest diameter of the chest, in seated position

- waist circumference measured in upright position

- Modified Mallampati class measured in resting seated position, with craniofacial extension measures

In pregnant women with SDB their neck circumference was significantly higher when they had a higher Mallampati class – with class 2/3 (red zone, neck circumference=37.85cm) and class 4 (green zone, circumference = 36.8cm) compared to participants with Mallampati class 1 (blue zone, 35.05cm).

This study also found a relationship between higher BMI, neck circumference, breast circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio with SDB. Interestingly women with Mallampati class 1 saw a higher risk of having SDB by more than twofold for every unit increase in neck circumference.

The Mallampati classification system, originally described to predict difficult intubations is dependent on tongue volume, mandibular size, and pharyngeal crowding. However, neck circumference is a reproducible measure that assesses a more distal area in the upper airway.

Both Mallampati class and neck circumference are influenced by fat deposition and fluid shifts. Even though obesity is an important contributing factor to OSA because of peripharyngeal fat accumulation and an increase in neck circumference it only accounts for a small portion of the variability of the frequency of SDB.

Therefore, the variability in SDB severity during pregnancy will be influenced by other factors including more complex variations in facial cephalometry eg nasal width, retrognathism, prognathism

A limitation of this study was the evaluation occurred only during the first trimester. As pregnancy is a dynamic state these findings probably do not apply to later stages of gestation. It also remains unclear how changing sex hormones influence airway collapsibility and impedance as they relate to SDB.

Future studies are being planned to examine the predictive ability of these measures in late gestation.

The risk of sleep apnoea are becoming increasingly well identified, and may continue to become more prevalent in Australia as body weight increases in our population.

References;

Anthropometric measures and prediction of maternal sleep-disordered breathing. Bourjeily G et al J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(6):849–856.

www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/maternityservicesplan